(305)

(306)

(310)

The specific term is coined in Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe (1819); “I offered Richard the service of my Free Lances, and he refused them”. Source: Merriam-Webster

(312)

– Marks’ Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers

https://www.cohenvanbalen.com/work/75-watt#

(313)

(316)

https://patents.google.com/patent/US9881276B2/en?q=(wrist)&inventor=Jonathan+Cohn&oq=Jonathan+Cohn+wrist

(317)

(318)

You know who they are. You have some names in your head right now.

(319)

https://othermeans.us/projects/things-words-consequences

(320)

(322)

(323)

(324)

(326)

“The project for CARA’s lobby/bookstore follows a simple, if tender, idea: room for everybody. Aligned with CARA’s vision, there is also room for fun and lightness. Chairs and tables in different sizes play with scale, challenging the standard furniture parameters. These nesting furniture, mixed with velvety geometric cushions, appeal to each while allowing flexible and playful uses of the space. The simple shapes and materials resemble the clean architecture while the color palette, derived from the dynamic logo, opens the door to other dialogues, a conceptual foyer of sorts for the voices to be housed by CARA.”

https://manuelraeder.com/project/cara-the-center-for-art-research-and-alliances/

(327)

(328)

Counter Power: Making Change Happen (2011) by Tim Gee: “Counterpower’s mission is to map political movements and understand how change happens, to ‘delve into the archive of history and try to learn from movements past to understand better what makes a campaign successful.”

(329)

(330)

(332)

(333)

(334)

Paralleling this to the often extractive inclination of university institutions to exoticise a student cohort in the pursuit of profit for consumption for middle class audience; Noam Youngrak Son highlights that often, the personal is the political. Read more in their interview from chapter 2: Self.

(335)

In the UK currently, pursuing design and creative careers at university is actively being discouraged by the conservative government as they label courses within the arts and humanities as “low-value degrees’, and enforce student number caps – a move that will disproportionately affect students from minority and lower-income backgrounds.

(336)

(337)

Co-Founder and Director of Innovation at Greater Good Studio. Full Professor (Adj) at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Full article here https://medium.com/greater-good-studio/design-educations-big-gap-understanding-the-role-of-power-1ee1756b7f08

(338)

Invited Tangle Speaker Laura Pappa documents such challenges to normative hierarchies through her publication series “Exercises in Practical Mischievery” – a collection that “chronicles the stories of notable individuals who have implemented out of the ordinary forms for the distribution of word and thought” serving as “an archive for freely accessible tools that facilitate the dissemination of thought.”

(339)

Such as the ending of legacy admissions for some US colleges.

(340)

(341)

Nelly Ben Hayoun is a French designer, activist, artist, etc. and founder of the University of the Underground

(342)

The CARA library, Interior design by Manuel Raeder. Visual identity by another past POST speaker, The Rodina.

(307)

(308)

While copyright law gives software authors control over copying, distribution and modification of their works, the goal of copyleft is to give all users of the work the freedom to carry out all of these activities.

These freedoms (from the Free Software Definition) include:

- Freedom 0: the freedom to use the work

- Freedom 1: the freedom to study the work

- Freedom 2: the freedom to copy and share the work with others

- Freedom 3: the freedom to modify the work, and the freedom to distribute modified and therefore derivative works.

Read more on copyleft.org

(309)

(311)

(314)

(321)

Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World by Keller Easterling. Verso Press.

POWER

Essay by Bethany Rigby

September 2023

“I want to be part of the people that make meaning, not the thing that’s made. I want to do the imagining, I don’t want to be the idea…does that make sense?” Stereotypical Barbie, Barbie, 2023 (film)

INTRODUCTION

Being uniquely positioned as those who have a hand in producing our environment; responsibility can be placed upon designers and the power they hold in changing the world for the future. However; power is an elusive and plastic substance that clings to some and slips away from others. While this text won’t comprehensively cover how design and power intertwine or undertake a thorough historical perspective, it aims to discuss moments where design and power intersect. The exploration will touch on contradictions and parallels that emerge from these interactions. Like design itself, power reaches into multiple systems and disciplines- so the following thoughts have taken root in previous chapters of the tangle; examining power through practice, self and community. Along the way, you’ll find case-study diptychs, serving not as reductive comparisons of good vs evil, but instead to illustrate complexities that arise when design and power meet.

WAYS OF WORKING

The lifelong career landscape of previous generations has evolved into a more dynamic era. Shifting employee and employer loyalty combined with a more turbulent landscape of the cost-of-living crises that squeeze incomes mean that the once linear path of employment has given way to a multi-faceted approach, where an individual could accrue a number of diverse roles, perhaps even in the span of a single day. Flexibility has emerged as a top priority for modern workers and has given rise to the ‘gig-economy’. The concept of “freelance” originates from mediaeval warfare, where mercenaries could be hired out to the highest bidder, and in recent years the rise in gigging marketplace apps (like Fiverr) have turned the freedom-filled freelance landscape into more of a competitive battlefield strewn with low hourly wages and tight deadlines. Design work can begin to slip away from a honed craft and into something more resembling a risky production line, often at the expense of the worker’s mental and physical wellbeing.

An emphasis on reducing timescales and costs can be witnessed across many stages of the design process, and designers have played no small part in creating and facilitating contemporary work environments through the design of production lines, technologies and behind-the-scenes systems intended to maximise human efficiency. Specifically within factory environments, the increase of mechanised factories and networked labour systems the lines between human and machine become increasingly blurred: customer, smart phone, doorbell cam, delivery driver, electric bike, efficiency monitors, robotic factory pickers, floor supervisors. An interwoven ecology of electronics and bodies making profit for their employers. In their experimental art practice, duo Tuur Van Balen and Revital Cohen- examine the nature of mass manufacturing and the bio-political condition of the human body as part of production lines through their project 75 Watts. This work develops a choreography of mechanical movements interpreted into dance within the context of a manufacturing plant in China. This discourse on the body-as-machine is also echoed in discussions around the value and rights of gig economy workers, and opens a space to examine what it means to be a designer, a worker, or a maker within the economic structures of today. As members of the design community, how can we use our skills as a way to disrupt exploitative labour practices?

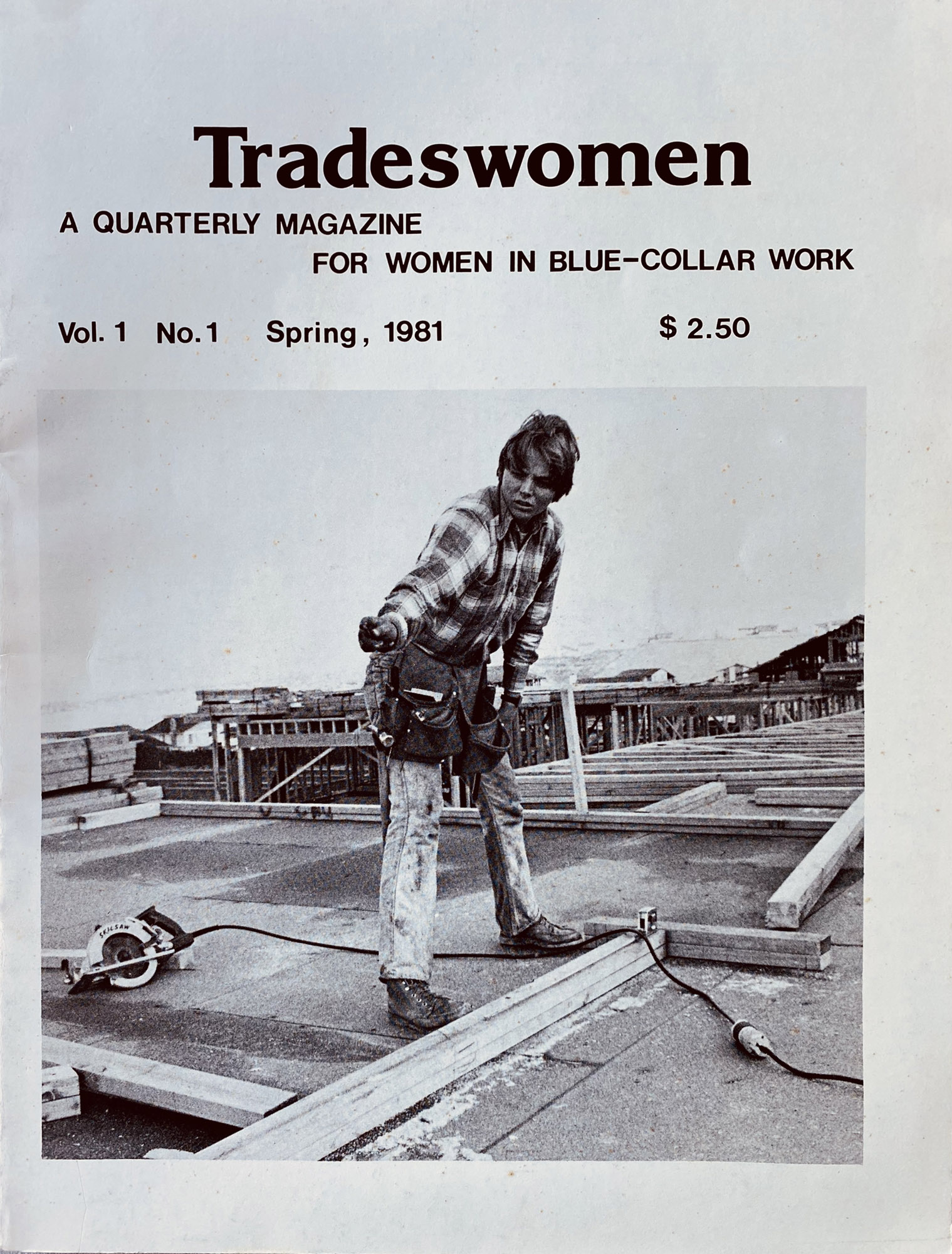

Case study 1: Recording the Worker

Tradeswoman Magazine: was a subscription publication produced for and by female blue-collar workers in the United States in between 1980-1990 and served as a platform and outlet for the experiences of harassment and discrimination they faced on a daily basis, as well as disseminating legal advice. “The simplicity of the design — with its white backgrounds, focus on photography, and easy-to-read type — is an important reminder that publishing as a form of activism is defined by clarity and urgency, above all else.” Molly Martin, Founder.

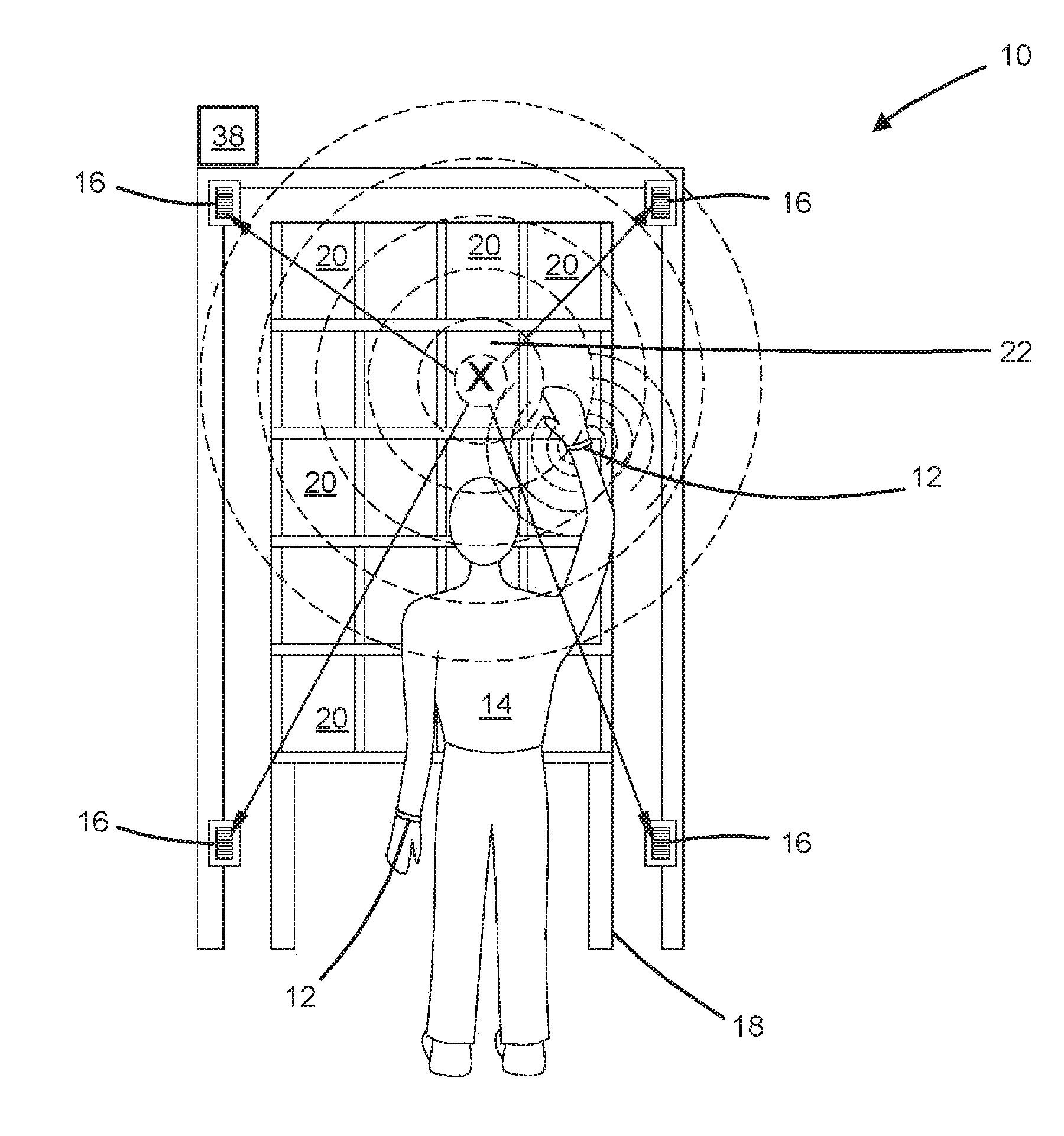

Amazon Wrist Monitor: In 2016, Amazon Technologies filed a patent for a bracelet to be worn by their factory workers. The bracelet would be calibrated to the shelves of the factory, and use ultrasonic sensors to monitor performance with vibration to indicate where products are in relation to the worker. These designs, and other devices currently in use, form a suite of surveillance technologies which at their best intend to increase efficiency and remove unnecessary tasks within the factory, but also record and send data to supervisors– often leading to extreme stress and anxiety in workers.

DESIGN AND CAPITALISM

Under capitalism, all production is in service to the economic market, everything is privately owned, and everyone works for a wage, it is a structure that spans borders and nations. Intended to foster individual prosperity and healthy competition, this model has instead resulted in greedy inequalities that harm people and the planet, while breeding corporate monopolies that amass socioeconomic power that rivals entire nations (Google, Microsoft, and Apple are a few that might come to mind). Within design culture, competition and celebration of individual success has coalesced into the emergence of “star designers” – celebrities, creative geniuses, design heroes, household names. However, this spotlighting of the headline (often straight, white, male) designer discounts the shared labour that it takes to enact works of design. Every iconic design we know and love today was helped along on its path to stardom by a branching network of collaborators, assistants, project managers, makers and facilitators. A vital goal for design today should be to broaden the voices that make up its chorus; not diminish them.

CONTROLLING IMAGE AND MEANING

Manipulating image + text to generate meaning sits at the core of visual design, and understanding how a piece of design (be that an object, a poster, etc) is read and responded to is fundamental in creating successful and memorable works. Every person brings along their own cultural and social perspective of course, both designer and user, but the overall study of how we ‘read’ the world is semiotics. For example; If you hear the word ‘Apple’; what do you think of? Rather than the familiar fruit, many of us will conjure images of the anodised aluminium bitten logo of Apple Inc. So strong is their monopoly over this word, that it has partially eclipsed the word’s original meaning. In order to maintain and reinforce this symbolic link, Apple conducts a fierce legal strategy of aggressively targeting businesses whose logo resembles an apple… or a pear, or pineapple, or other fruits. The brand is rigorous in the defence of their semiotic control.

Case Study 2: Inscribed Tablets

Apple ipad: The ipad, first released in 2010 was Apple’s major venture into tablet based computers. Although less powerful and more expensive than a laptop, many favoured the intuitive engagement with technology that it enabled. On the other hand, many users accidentally destroyed their ipads after being fooled into believing certain updates would make the tablet waterproof, or be able to be used as a weighing scale. Oops.

Clay tablet: Since the Iron Age, slabs of wet clay were used as a writing medium as early as 2000BC. Scribes would engrave things like epic tales, receipts, recipes and laws into the clay, which could then be re-used if the slab was washed in water. In his book “CAPS LOCK”, Ruben Pater parallels these early writers as the first graphic designers. “Scribes had to master skills such as constant mark making and ordering of information on small surfaces.

Inscribed on the back of most Apple products (including the laptop into which this essay is being typed) are the words “Designed in California, Assembled in China”. This intentional separation seems to indicate a distinct severance between each geographies and modes of production. “Designed in California” places emphasis on the product’s American conception, perhaps in order to increase the perceived value of the product. On the flipside; “Assembled in China” distinguishes that the manufacturing of the product is far removed from Silicon Valley. This segregation linguistically – and therefore ideologically – distances Apple (recognised as a ‘design’ company, not an ‘assembling’ company) from the problematic manufacturing practices that occur within its supply chain. What are the responsibilities of a designer over the entire design process? What is the agency that their designs have in the world? Do materials themselves inherently hold the memory of their production?

THE AGENCY OF OBJECTS AND THEIR MAKERS

This section grapples with these questions – attempting to understand the separations between designer, and the designed- the idea and the imaginings. When products or buildings work as they should such questions are rarely raised, but when something goes wrong, and perhaps lawyers become involved- the issue of defining responsibility (and therefore who held the power) is at play. The tragedy of the Grenfell Tower Fire in London six years ago has triggered a discourse around responsibility – or irresponsibility – of materials, designs, and their designers. The ongoing inquiry into the fire has attempted to assign responsibility for the use of unsafe flammable cladding and evacuation systems in the Kensington tower block. In one hearing a draughtsman explicitly disputes the word ‘designer’ that he believes was incorrectly assigned to him on his company business card; “You don’t want to read too much into that term,” he said. “There’s a general consensus that once you put the word ‘designer’ in there there’s an element of responsibility, far more than maybe there should be.”

Case Study 3: Material Agency of Laminated Plywood

Eames Lounge Chair: As pioneers of iconic furniture design in the 1950’s, Charles and Ray Eames sought to create affordable, mass produced furniture with laminated plywood– a material that uniquely combined strength, mouldability, cost-effectiveness, low weight and an attractive finish. A larger version of the chair has been released to reflect the average human height increasing globally by 10cm.

AK47 (Avtomat Kalashnikova): In the same decade as the release of the Eames Lounge Chair, laminated plywood began to be used in the Type 3 AK47 to enable faster and cheaper production of the gas-operated automatic rifles. The engineered wood was used for the ‘furniture’ parts of the rifle: the buttstock, lower handguard and upper heatguard.

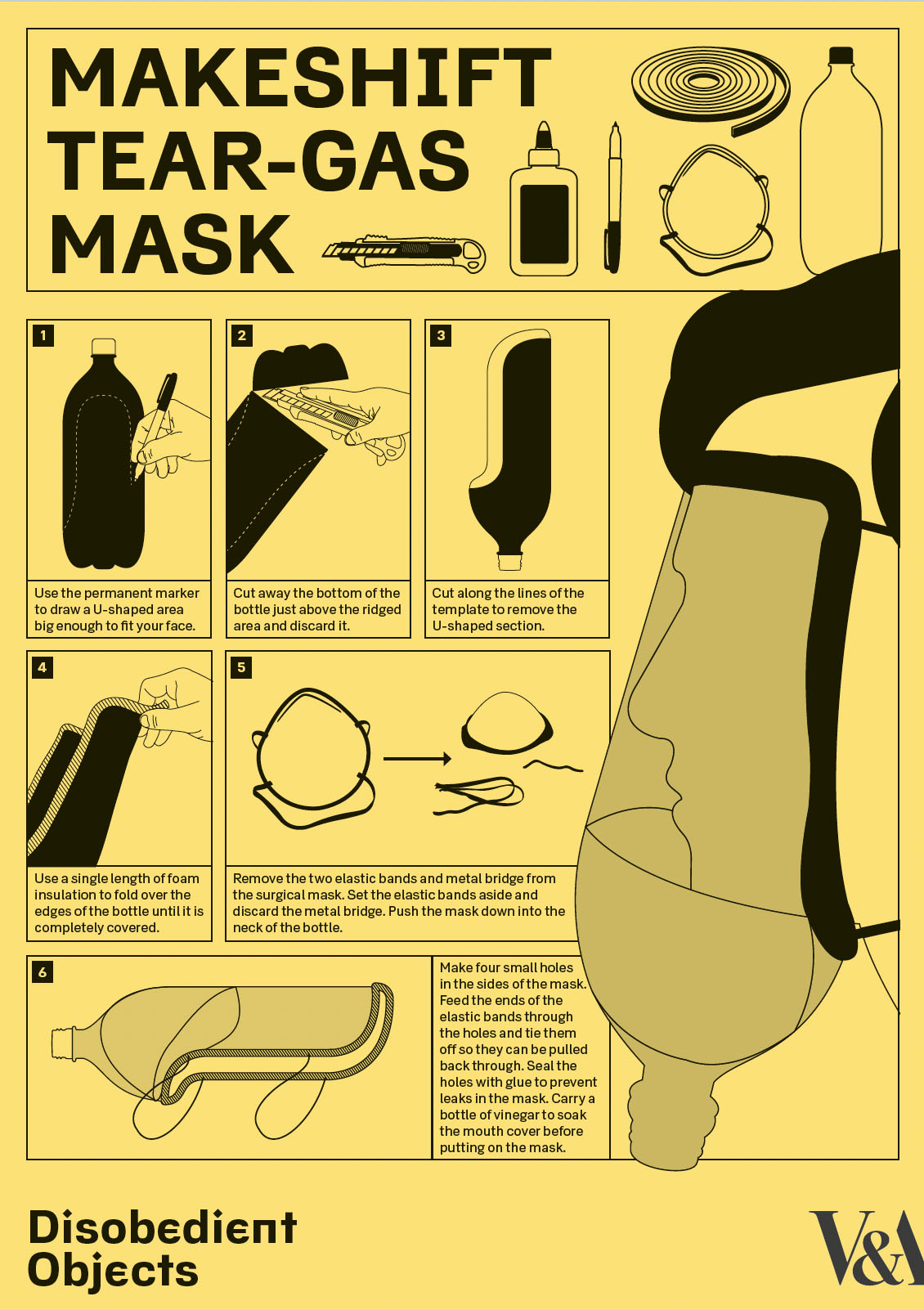

Power exerted or expressed through an object/material and its relationship with designers was examined at the V&A Museum’s 2014 exhibition and accompanying book Disobedient Objects: “Disobedient objects have a history as long as social struggle itself. Ordinary people have always used them to exert ‘counter-power’”. Unravelling the histories of social movements under the lens of material culture and designed objects– a previously under-looked area compared to that of printmaking (such as social posters), performance or music– begins to acknowledge the networks of bottom-up, everyday acts of resourcefulness that is required for successful activism to take place. This complex network of making and un-making is defined as an ‘ecology of agency’- and in the same year of the exhibition, the V&A established a new form of collection, the Rapid Response Collection, where objects of immediate and contemporary design importance (as opposed to importance realised after gazing, misty-eyed, through the past) are introduced to the museums permanent collections in response to significant moments “either because they advance what design can do, or because they reveal truths about how we live.”

“Disobedient Objects reveals design to be much more than just a professional practice or a commercial process. It shows that even with limited resources, ordinary people can take design into their own hands. It celebrates the creative ‘disobedience’ of designers and makers who question the rules” Martin Roth, Director, Victoria and Albert Museum. Disobedient Objects (book) 2014.

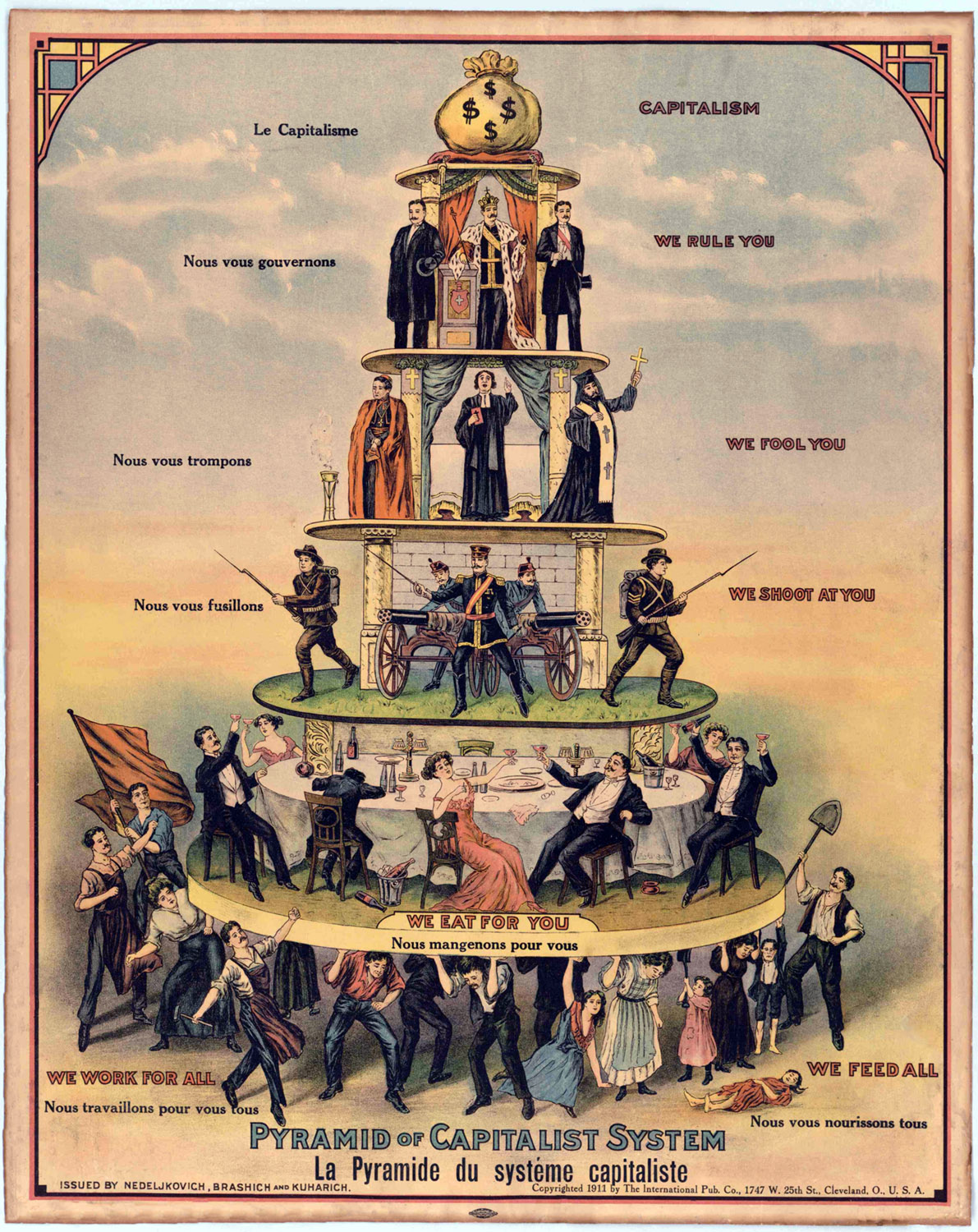

THE SHAPE OF– AND SHAPING– POWER STRUCTURES

Power, as British philosopher Bertrand Russell defined it, is simply “the ability to produce intended effects.” This ability, however, can be slippery and elusive, or concrete and firmly assigned, depending on who and where you are. Historically and in most places today, a prevalent power structure takes a hierarchical shape- with a minority in control at the summit exerting authority over the majority below (think of a pyramid as a visual analogy). This top-down structure favours those already in power; reinforcing inequalities and impending upward social mobility. This cyclical nature of dominance is often reflected in our institutions of knowledge such as universities – usually the place where many designers will cut their teeth and find their place in the creative world. As centres of knowledge production, universities are uniquely placed for shaping both the technical skill and social perspectives of future designers. Many find their universities a more diverse environment to where they grew up and an empathetic incubator for emerging creative talents, but with increasing expenses and tuition fees, higher education is becoming a privilege few can afford- yet again reinforcing the inequalities of social mobility. As examined by Professor George Aye; a basic understanding of how power operates is lacking in design education: “This lack of understanding by design students and design teachers results in wasted funding, poorly prioritised projects, and broken promises to the very communities that are being served.”

Being a forward-facing and collaborative discipline at heart; design is conveniently positioned to introduce radical approaches to education that directly challenge established social hierarchies and mechanisms of knowledge distribution. Although there are some strives within established higher education institutions to remove historical blockades to access – alternative educational platforms such as the University of the Underground, AntiUniversity, CARA (the Center for Art, Research and Alliances), along with numerous summer school programmes can react in more immediate and radical ways to the inequalities in access to design education. Designer and activist Nelly Ben Hayoun encourages her students to positively challenge established institutions: “The way you can address power structures is by teaching students how to identify them in the first place by using political theory, like that of Hannah Arendt, so they can find a way inside leadership positions”. To borrow some words from the project brief of Manuel Raeder’s work with CARA; in design education, there should be “room for everybody”.

Incorporating voices from underrepresented communities is vital to redistributing power within the design industry in order to reflect the world that we are designing for, and for decentralising power across communities. Open-source methods of knowledge sharing help promote more equitable access to good design- such as Copyleft; a legal technique that allows work to be used, modified and distributed for any purpose without a fee (as opposed to the more widely used Copyright; which restricts such use), and international non-profit organisations such as Creative Commons. Historically; designers have also come together to form unions in order to protect workers rights- and in fact; the first US trade union was the International Typographic Union who spearheaded employment campaigns such as the 40-hour working week. Today, almost 172 years later, an upcoming workshop ran by Tangle alumni Noam Youngrak Son entitled “The Union For Unvalorised (Design) Labors” will “use speculative design methodologies to tackle some inherent and inherited issues” of the freelance labour landscape of today.

Case Study 4: Community Consensus

Twitter > X: Often referred to as the most powerful person in the world; Elon Musk, is the owner of the social media platform “X” (formerly known as Twitter). In a string of tweets, he orchestrated a crowdsourced overnight redesign of the platform’s blue bird logo via a community open-call for submissions (the winning logo was a minimalist letter designed by Alex Tourville). For a large brand with millions of users- this is a chaotic approach compared to rigorous design processes usually employed for such decisions.

X’y McX-Face: In 2016, the British public voted to name a £200 million polar research vessel “Boaty McBoatface”, a joyful example of humour when power is handed over to the internet community. The “McFace” spoof has become somewhat of a social phenomenon, with a racehorse, snow-plow and a skate park among the newly named-by-public-poll. Humour, jokes and satire have long been utilised as powerful methods of visual communication – as Metahaven examines – the maker of a joke is “truly a designer”, stating “the joke has untapped power to disrupt – a power far greater than we thought.”

REACHING IN, REACHING OUT

The power of design is in its ability to reach out of itself and into other disciplines– this is what makes it a radical practice. It not only imagines the future, but plays a major role in enacting, realising and physically making that future. Every designer will bring their own biases and experiences to every project they work on and will be influenced by the economic, political and social structures that are the context within which they operate. As such; the threads of power form an immensely complex tangle that can be difficult to unpick- let alone to weave into a new tapestry. When we turn away from competition and seek alternative models of sharing, teaching and practising design- we can together work towards building more equitable systems for all, inside and outside design. Embrace the messiness and imperfections, trust in the unknowns. To end in the words of Keller Esterling– who’s quote not only reflects these sentiments but also encapsulates the intentions behind the POST.Design Festival and this editorial platform: “Designing is not solving but further entangling.”

Back to grid