(45)

(46)

Narcissus and Echo, Danny Burk, 2001.

Source: Cornell College

(47)

Mirror Test. Wikipedia.

Image source: wikipedia

(48)

Beyond the Self, Jack Self, e-flux, 2016.

(49)

Anthropocene Hubris, Stephanie Wakefield, e-flux, 2020.

(50)

For more information: Simply Psychology

(51)

Superhumanity: Design of the Self. Nick Axel et al. e-flux architecture. 2018.

(52)

The Self Design Committee: How a face filter might or might not democratise self-design. Noam Youngrak Son. 2020.

(53)

Ontological Design has become influential in Design Academia- but what is it? JP Hartnett. AIGA Eye on Design. 2021.

(54)

Epochal Aesthetics, Kathryn Yusoff, More than Human, 2021.

(55)

On Hybridity, Daisy Halyard, 2022.

(56)

Atmospheres of the Undead, Caitlin Berrigan, MARCH Journal.

(58)

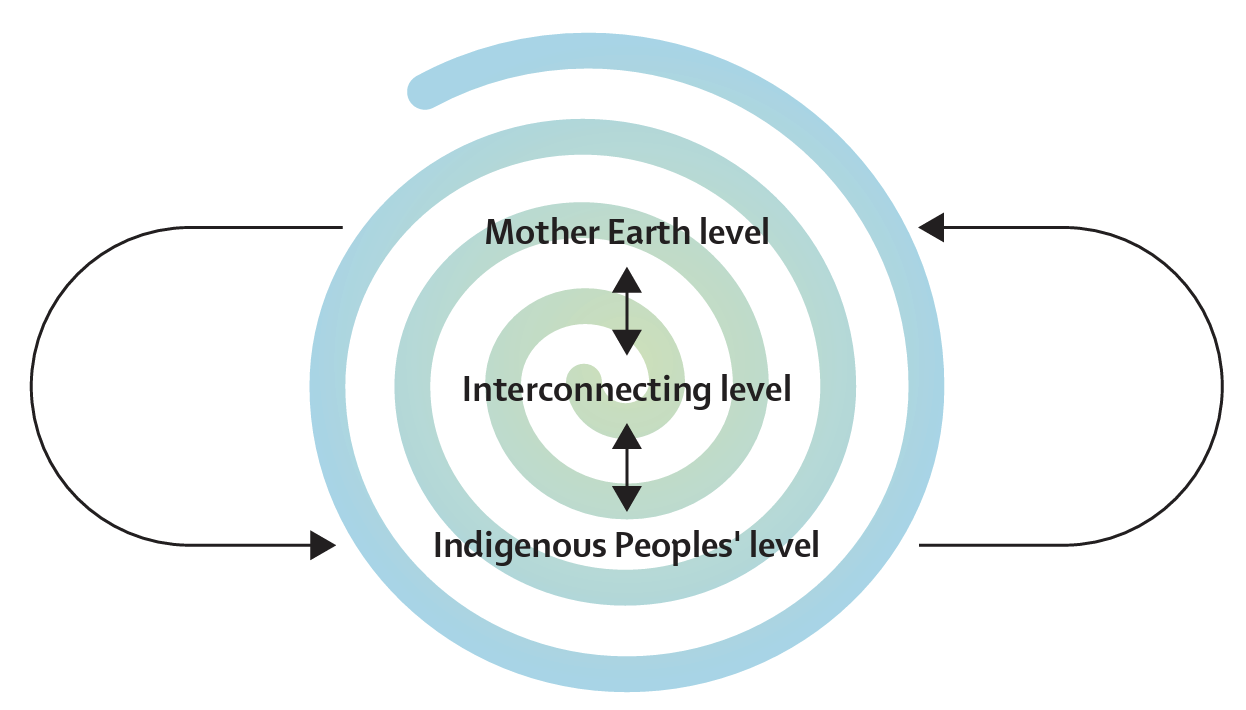

The determinants of planetary health: an Indigenous consensus perspective, Nicole Redvers et al. The Lancet, 2022

(59)

When Species Meet, Donna J Haraway. 2007. University of Minnesota Press.

(60)

3rd Istanbul Design Biennial 2016 – manifesto

(57)

Beyond the Self, Jack Self, e-flux, 2016.

(61)

The Self Design Committee: How a face filter might or might not democratise self-design. Noam Youngrak Son. 2020.

(62)

Quote by Boris Groys in Superhumanity: Design of the Self. Nick Axel et al. e-flux architecture. 2018.

(63)

(64)

(65)

(66)

Writer John Green has written a lot of essays under the umbrella concept of reviewing facets of the human-centered planet on a five-star scale — rating things in itself being kind of a peak Anthropocene thing to do. The essays can be heard in podcast form as The Anthropocene Reviewed and also exist in a book by the same name.

(67)

In Noam Youngrak Son’s workshop “Chimera Gastronomy: Malleable flesh, amalgamated bodies, and plastic kinship” the group will work individually and collectively on a large malleable body sculpture.

(68)

(69)

The podcast Flash Forward has a really great episode exploring the history and concept of “Environmental Personhood” through concrete cases and interviews with the people currently dealing with this legal term in practice.

(70)

“As a gender star, the asterisk acts as a kind of joint, between endings and among genders. Though “hack” may sound like something’s breaking, the asterisk in this sense is a tool for mending, or at least for tenuously holding things together until something better arises.“ – Meg Miller via Source Type

(71)

(72)

Narcissus, Neoliberalism and Interconnectedness – a dive into the entangled Self

An unfurling essay by Bethany Rigby

September 2022

A dive into the cultural, social, political and ecological ‘self’, questioning the notion of the ‘individual’ and a call towards connected ways of being.

PART I: ISOLATING THE INDIVIDUAL

“One day while Narcissus was hunting he went to get a drink. As he bent down to drink the water he fell in love with the reflection of himself. He was so awed by this person that he could not move. He tried to grab the image but couldn’t, which made him more infatuated with himself.

Narcissus stayed there without any sleep or food. He called to the gods asking why he was being denied the love that the two shared. He started to talk to the reflection. He claimed he would not leave the one he loved and that they would die as one.

Crazy with love, Narcissus stayed by the side of the water and wasted away. He said his farewell to the reflection and Narcissus then lay down to die and the nymphs mourned him. They covered him with their hair and set up for a funeral. When they turned to his body, there was a flower instead.”

The mythology of narcissus, the hunter so in love with his own reflection that he starved at the riverbank, is thought to have stemmed from the ancient Greek superstition that it was unlucky to see one’s own image reflected back at you. The concept of the ‘individual’, or individualism, is a relatively modern view; the Greeks instead epitomised community life; that humans are suited naturally in particular to living in a polis, or city, and any person not living in this way would fail to realise their full ‘humanness’. Aristotle taught that anyone not living in a polis must be either a beast or a god; less-than-human (beast) due to falling short of their human potential possible when living in a polis, or more-than-human (god) as they would need to be living completely self-sufficiently from others. The question of whether certain peoples are considered beastly or godly has shaped social hierarchies for centuries in the uniquely human drive to philosophically understand ourselves. What makes me different from you?

Human beings today are genetically indistinguishable from those that existed 200,000 years ago. Although the genetic code locked within our DNA remains the same, it is almost impossible to compare modern humans to our ancestral beginnings. Instead, behavioural evolution is what has enabled the proliferation of humans as a species across the globe and into every climate to become the only species to enact ecological change on a planetary scale. The context of our existence and the technologies and structures that surround people living in urban places would be unrecognisable to an ancestor. There are some behaviours that still feel deeply ancestral- climbing up on something tall to see something far away, feeling the sun on your face, brushing a bug off a friend- but overall, the complexity and distraction of daily life is widening the disconnect to this deep linear heritage of humankind. It is unlikely that an ancestor of mine would recognise my reflection in a river, or my likeness caught in the more probable medium; a selfie.

Very few species have passed the ‘mirror self recognition test’ (MSR)- a traditional visual test for measuring physiological and cognitive self awareness by placing a coloured marker on the animal and seeing if, when catching its reflection in a mirror, it tries to remove the mark. Animals that have passed this test include gorillas, chimpanzees, a single asian elephant, rays, dolphins, orcas, the eurasian magpie, and the cleaner wrasse. In humans, from 6-12 months babies typically see their reflection as a ‘sociable playmate’, followed by self admiration and embarrassment appearing at 12 months, and from 14-20 months children demonstrate avoidance behaviours, and by 18 months about 50% of children can recognise themselves. From infancy we begin to create ourselves, a process that is shaped by the socio-political currents that we swim within.

In the political present of many euro-centric countries there is a prioritisation of the individual over the collective. Such places actively encourage self determination and a drive towards individualism as the best route to personal success. “Today, the individual has been transformed into a purely economic agent: rational, dumb and self-interested.” There are numerous ways in which this is manifesting: we are told tales of our individual power as voters, economic agency as consumers and gradually, the scaffolds of collective action are dismantled. In policy, this is demonstrated by the increasing inclination of governments to ban the formation of unions and acts of protest as a way for communities to come together. The ‘American Dream’ epitomises that relentless self betterment is always possible regardless of social class or living situation; it professes that we can create the life we dream of with hard graft and determination. Although this may be true for some, overall neoliberalism has slowly eroded away at the concept of community in favour of competition. The notion of ‘the individual self’ which once promised freedom, and is now the mechanism of our subjugation and control.

Following the past few years of crises, Stephanie Wakefield notes: “one might observe that there seems to be a growing tendency toward “delinking” or “islandization” in response to Anthropocene conditions and events. For example, politicians promote ever-more securitized borders and walls as a manipulative solution to the suffering of working-class people.” Wakefield points to this “islandisation” in the continued use of off-shore tax havens, gated communities and proliferation of underground bunkers, and even to the interplanetary escape routes spearheaded by Elon Musk’s martian ventures and numerous other privatised space colonisation projects. On a more day-to-day level, increased isolation of the individual can be observed in more subtle ways such as the increasing popularity of ‘self care’ routines stepping in as a substitute for crumbling welfare states with long waiting lists.

The current epidemic of loneliness, and also the cementation of socio-cultural tropes in the media such as single mums, lone wolves, and digital nomads. Cumulatively, these examples work against the past evolution of human behaviour that was nurtured by connections, collaborations and kinship. They instead form an unusual hierarchy seeming to demonstrate that self betterment is achievable and should be prioritised regardless of the conditions of our immediate environment. This view is in opposition to that of Maslow’s Pyramid of Needs which dictates foundational needs of food, rest and safety are followed by love and belonging, with prestige, self esteem and self actualisation finally occuring at the summit only after all other requirements are met.

The familiar world of modern humans in which we now exist is at the threshold of the Anthropocene- a uniquely narcissistic and self-centred epoch of our own making. Here the word “our” denotes the polluting population of humankind- to acknowledge that not all humans have caused the Anthropocene. This moment we find ourselves in is a feedback loop, where we create our environment and that in turn creates us. In this process, known as ontological design, creative practitioners find themselves as active agents through the design of new behaviours, tools and technologies. As summarised by Boris Groys: “The ultimate problem of design concerns not how I design the world outside, but how I design myself- or, rather how I deal with the way in which the world designs me.”

Engaging in the theory of ontological design enables an excavation of the ‘self’; if we examine the world in which we find ourselves- a world where identity and commodity have become increasingly synonymous- it becomes easier to perceive where the concept of ‘the individual’ sits within larger structures of community or collaboration. In Noam Youngrak Son’s The Self Design Committee, they confront the concept of individualism and hijack the notion of self design by feeding it into a community structure; “in the case of my identity, which is not solely mine, self-design becomes a collective task performed by distributed agents.” Often, grappling with the concept of the self conversely highlights the complex interconnections we build with those around us.

PART II: TOWARDS ENTANGLEMENT

The impending climate crisis of the Anthropocene disproves the neoliberal vision of permanent progression; forms of life tied to and lived through fossil fuels stand on a precipice- and at close inspection; new forms of entanglement growing from the urgency of this moment can be observed. Despite the political framework many of us exist within as outlined previously- humans are innately collaborative creatures on a social level and also on a bodily, cellular level. Human intimacies with the non-human are constantly evolving with accumulations and assemblages taking place.

In some ways, we can see on a purely biological level that our built environment is, in turn, building us; air pollution damages DNA in lung cells, forever chemicals reside within organs, residues of heavy metals build inside tissues, and microplastics have been found in 80% of human blood. The living and non living blur together. On a more macro level, there are machines interacting with and within us; pacemakers, microchips, screens and fingerprint scanners. “We are all robots now”. We are becoming silicone. Our digital selves become intertwined with the physical; enabling us to become something beyond the boundaries of gender, race, age, or species.

A re-organisation of machine and human is explored within Nushin Yazdani’s Dreaming Beyond AI, where the platform itself and the process through which it is created challenge deeply rooted ways of thinking, knowing and being in the digital realm in to ‘dream beyond’ predictable futures. By dissolving the hard borders of what being ‘human’ is, and what an ‘individual’ is, we open ourselves up to new possibilities of existence beyond what is becoming possible across physical scales. The global cocoon of undersea cables and orbital satellites condense geographical space and time into inches (screen to face) and milliseconds (send and receive), where a viral dispersal of knowledge (both factual and fictional) through a network of interconnected devices takes place.

We often reach for search engines before resolving a debate through conversation, and we turn to mapping apps rather than trust or test our navigational intuition. Does this make it easier, or harder to truly know ourselves? Mirroring the physical toxic accumulations within our bodies, minds also become harbours for increasingly radicalised thought. Concentrations of toxicity seep from digital spaces into physical and back again. We increase our capacity, our capabilities. We become more-than-human, we become vibrations moving through the sea, sky, space and screen. “We become atmospheres.”

So what makes a person? As humans and their environment become physically and intellectually intertwined in the Anthropocene, there is a concurrent recognition of specific identities in ecological, non-human beings. Environmental Personhood is the legal concept that designates entities with that of a legal person including rights, protections, privileges and liabilities. Although a relatively recent legislative movement across the areas of USA, Australia, Canada, India and South America, the meaningful recognition of ecological entities beyond that of something to extract and exploit is nothing new. Indigenous ontologies (ways of being) and epistemologies (ways of knowing) are intimately connected with the Land, and Indigenous perspectives are “therefore in direct contrast to the human-centric worldview that continues to permeate climate discourse and action”.

Stepping away from the human-centric, anthropocentric view of ourselves enables the vital re-organisation of hierarchies to begin reparative, more humble, collaborations. A necessary step of thinking past the centrality of the human subject is to re-configure what being human is. Only 10% of all the cells in the human body contain human genomes. The remaining 90% belong to fungi, bacteria, protists, some which are vital and others harmlessly hitchhiking as explored by Donna Haraway in When Species Meet, where she states “to become one is always to become with many.”

Creative practitioners can mobilise this through their processes; we may be designing for humans- even perhaps a single specific human in some cases- but recognising that we are all part of an interconnected web- a tangle- of ecological, geological and geographical beings on par with one another rather than above them- creates not only a kinder, but a necessary, deeper connection between ourselves and what we create (as we simply cannot get around the fact that these creations will, in turn, create us).

PART III: SHARED RICHES

We are already assemblages of beings, human and non-human, living and non-living working in tandem. Cyborgs, robots, holobionts, collaborators. This adjustment of perspective may lead to a less familiar, less recognisable self but one that is less isolated. It is as what happened to Narcissus when he gazed at his reflection and the self he knew died being replaced by a flower. The destruction of the self[-ish] perspective leaves space for new, more beautiful ideas to grow. In the current moment, rebelling against individualism and the politics surrounding it make collaboration a radical act. Seeking shared experiences within a creative practice can not only be generative, but seeing the world through the eyes of others is necessary to creating accessible and meaningful design, towards imagining new networks of selves interwoven together in messy and unexpected alliances.

Back to grid