(372)

(374)

(376)

The Cassandra team is Chiara Di Leone, Laura Cugusi, Anastasiia Noga. Cassandra is a research collective that investigates institutional practices and formal structures that emerge in the field of ecosystem governance. It explores how climate change is not only constructed through discourse and rhetoric, but produced through protocols of action, gestures, rituals and choreographies that corporate and state institutions routinely perform. In Building Earth’s Futures, Cassandra imagines a different way of conceiving the future habitability of Earth. It departs from the existing frameworks of scenario planning, which governmental and corporate entities use to strategize in the face of the ongoing climate collapse. Instead, it moves into the realm where past, present and future are intertwined in a complex mesh of cause and effect, addressing the climate narratives that are written before projections and after modelling.

Looking Back at Looking Forward

Interview with Chiara Di Leone

Speaker at chapter 4: Power

September 2023

Words by Bethany Rigby

Photography by Sanni Riihimäki

We caught up with Chiara after the Tangle to talk about the intersections between research and creative practice.

Mainstream communication of the climate crisis can sometimes hit the stumbling block of not conveying the immediate reality of our ecological situation (some may think it will happen later, some might deny climate change altogether) can, or does gaming– often an escape from reality– help bridge this gap between fiction and reality?

In general, I think the answer to your question is yes, gaming can be a very effective communication tool; it allows for greater complexity than text-based narratives alone and it creates opportunities for deeper experiences and a higher level of personal investment.

About climate communication, I have already written about the importance of conveying the urgency and violence of climate change. In that essay, I explore the challenge of narrating and communicating the climate crisis, pointing out the limitations of storytelling as a tool for understanding and addressing the complex, gradual, and dispersed nature of climate change. I try to problematize simplified narratives and discuss the attempt to simulate potential climate catastrophes in order to make them more comprehensible and evoke a response. However, I also question the effectiveness of this approach, highlighting that the planet is utterly indifferent to human storytelling. Despite efforts to create narrative-driven engagement with the climate crisis, real tragedies unfold, emphasizing the urgency of reevaluating the role of storytelling in addressing the climate emergency. Maybe we don’t need to “feel” or “experience” climate change, we need to do something about it.

In your introductory lecture you outlined the history of the “war game”, developed by European military strategists – a system of thinking that has two opposing sides – and a system that Half Earth is also based upon (if we understood correctly). How do you counter the imperial/adversarial dynamics embedded in this type of games for the purpose of something far more “entangled” like climate change justice?

Let me begin by clarifying that my work does not specifically address issues related to climate justice. While I recognize the significance of climate justice, it is not the central focus of my research. Instead, my work centers around the examination of how knowledge and technologies employed to comprehend intricate subjects, such as climate change, operate in the present and have functioned historically. As a result, I have delved into the study of games and predictive simulations as intellectual technologies, encompassing activities like scenario planning and wargaming, among others.

When we consider Prussian wargaming, specifically Kriegspiel, it involves two or more opposing factions striving to achieve victory by strategically overcoming their adversaries. This adversarial game structure aims to simulate military conflicts of the 19th century in Western Europe, capturing the strategic challenges prevalent during that era.

In contrast, the RAND Corporation’s Future Board Game (1966), which I briefly discussed in my presentation, introduces a different dynamic. In this game, players compete not against identifiable opponents like armies or fleets, as in traditional wargames, but rather against each other to make accurate predictions based on various variables, including the introduction of random future events using a hexagonal dice. The Future Board Game doesn’t depict a conventional enemy; instead, it exposes players to the more chaotic reality of existential threats that the game seeks to model, such as nuclear war, climate change, or dictatorships. It serves as a reflection of the anxieties prevalent during its time.

In the case of the Half Earth Socialism game, the player is not confronted with an explicit adversarial dynamic either. The player has the opportunity to try their luck at being a world planner by aiming to reach certain ecological and societal goals. I believe that is already a game dynamic that departs from adversarial approaches.

Writing forms a central part of your process- can you explain a little about how you approach writing as a creative practice?

I write and publish non-fiction essays, artist profiles, exhibition reviews and also write academic papers which are now under review. These are not normally considered texts of creative writing, but writing itself is a creative practice, though I don’t always think of it that way.

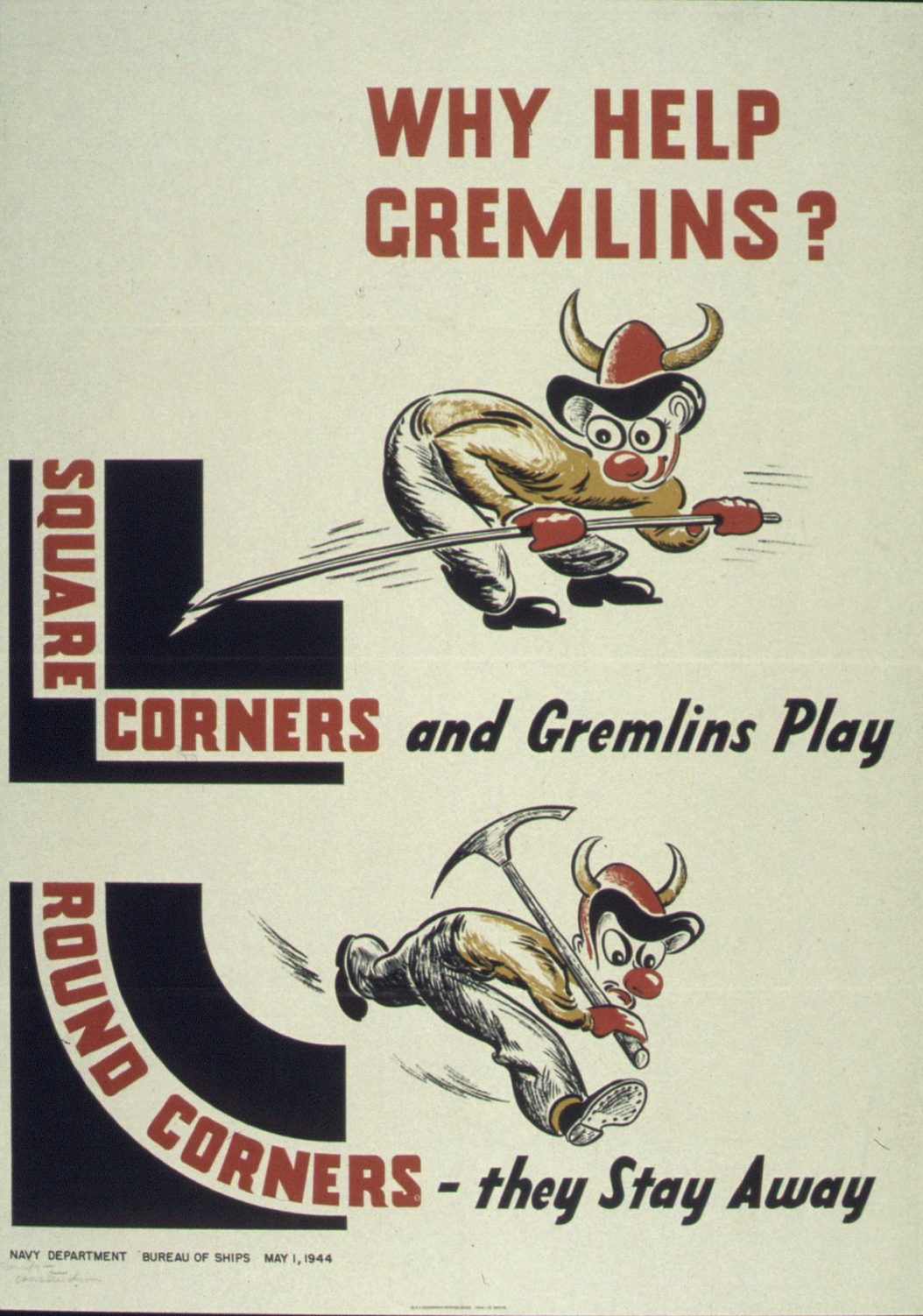

My approach to writing is quite dry and matter-of-factly. It always starts with a question I am trying to formulate, but I don’t know how to. So I would often read what more seasoned writers have to say on the topic, then go and read more niche secondary literature and, if I am lucky and have the resources, finally, I would go and interview key people and visit relevant archives. My approach to research is motivated by topics/questions that I find 1) urgent 2) underrated or under-researched and 3) fun to dig into. Even then, writing is always a drag: I have an internal critic residing in my brain: it is this horrible gremlin who loves to criticise my ideas and sometimes does not even let me start. As soon as I believe I have all the research elements figured out (and gremlin permitting) I try to just sit and write. Of course, that often leads to even more questions which lead back to the drawing board. Things do get done in the end, but it’s never a smooth process.

A much less troubling part of my work is technical writing: I have written documents for companies and NGOs and art organisations that simply explain or expand on someone else’s ideas. I find these tasks much easier to deal with, no gremlin involved.

I have never published creative writing, though that is something I would love to do one day. I’m very interested in screenwriting and short stories. I have written a few fictional stories which I hope to get out one day.

What are the future plans for Half Earth?

My role in the Half Earth Socialism Game was that of a humble reading group coordinator and researcher. I hope the designers of the game and the authors of the book will keep going as I do believe it to be a wonderful game which has already gathered a tremendous amount of support.

With your academic background in economy, how is it to work with designers and other speculative visual thinkers?

Studying economics and financial markets was definitely something that I hoped would stifle my brain, drain any artistic aspiration out of me and put me into a money making mode. This did not work very well. After a few years in banking and consulting, I became way too interested in writing. I started reading beautiful books in the History of Science and History of Social Sciences, mostly by Lorraine Daston, Ian Hacking, Philip Mirowski and Peter Galison. I also read a lot of design theory from Keller Easterling and Benjamin Bratton. When I learned about the Strelka School program in Moscow where Peter Galison was a guest teacher and it was led by Benjamin Bratton I decided to apply and I got accepted. That marked the end of my time on Microsoft Excel. I really wished I was a Microsoft Excel kind of girl, but I just was not. I went to Strelka and that changed my life. After that, everything was possible and everything got weird. I started making films and publishing essays and writing 1000 words a day. I loved it and I try to keep things that way.

Images have been very much present in my work, both in the sense that I have written about them (see my exhibition review of the American Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021) and I have worked with visual media. In 2020, for instance, I made a video essay about the IPCC and scenario planning. I am very interested in cinema and in screenwriting and sporadically write about films on my Substack, World-Smashing. I could infer that you are trying to ask me about collaborations with designers and artists. If that’s the case, I have been working quite productively with them, I think. With my Cassandra team (composed of another writer and an artist), we exhibited at the Tbilisi architecture Biennial and at the Dutch Design Week amongst other design contexts. (The video above is a clip from Cassandra’s work).

I remain invested in improving my writing craft and analytical thinking and hope that my writing and research can remain useful and inspiring to many different practitioners, including visual artists and designers. I am honoured to be able to collaborate with art and design practitioners — that is definitely something I want to keep doing.